Dreaming, Seeking, And Seeing The Opportunity

In Honour Of Master Wonhyo , My Father, and My Shifu

Shifu said:

“It was Master Wonhyo who taught "Balsim suhaeng jang" -- that is, "Awaken Your Mind and Practice". What does it mean to awaken the mind? Consider when you were a child -- you never craved sleep more than when your mother tried to get you up for studies.

Consider when, as a child, you never wanted the sun to set for fear it meant leaving the waterfront and the embrace of your mother. Consider when, as an older person now, you see sleep as a sweet place of dreams where you can return to that very same sunset -- and yet all the while the preciousness of your present existence, with the ability to have clarity, waits for you like a faithful beloved who gives you unconditional love.

The Dharma is that faithful beloved -- born of the Buddha, with the Sangha as its family -- as your family. How long will you stay sleeping? How long will you be a hesitant dreamer, and not actively seek the prime opportunity?”

The Story of the Hesitant Dreamer

There once was a child who lived in a coastal village, where the sea whispered secrets and the sun never seemed to tire of watching over the earth. He loved most the golden hour, when the sea turned to honey and his mother would wrap him in a towel smelling of salt and sandalwood, whispering, “It’s time to go home.”

He would cry each time—not from stubbornness, but from reverence. To leave the waves was to leave joy itself. “Just a little longer,” he’d plead, clutching his toy boat, eyes red but full of longing.

At night, that same boy would transform. When morning came and his mother called him to wake for his studies, he would roll deeper under the covers. “Let me sleep,” he’d mumble, as if the world had nothing to offer but burdens, and dreams were the only safe harbor.

Years passed, and the boy grew into a man.

He no longer cried when the sun set—he barely noticed. He no longer protested the morning—he had come to crave sleep instead, for in sleep he could return to that child, that mother, that sunset. The days were full of tasks. The nights, of regrets. He was weary in his soul, though his body walked and talked and did what the world asked.

One night, he dreamed again.

He was on the beach. The golden light was just as he remembered. His mother was there, smiling, but silent. As he approached, she did not embrace him. She turned and walked into the ocean. He called out, but the waves swallowed his voice. Desperate, he chased her, but the sand gave way and he fell.

When he awoke, he was crying—not for the past, but because he had wasted the present. Outside, the sun was rising.

A knock came at his door.

It was not his mother.

It was his teacher—his Shifu.

Carrying only his shakujo, having dropped all else, suffused by the soft scent of morning incense.

And Shifu said:

“The sea still waits, child — deep is the sea of the teaching.

But not for dreamers to dive in, only for the active seekers.

Awaken your mind, and practice.”

The Sick Man Who Dug for Poison As An Active Seeker

Shifu said:

"Listen again to what Master Wonhyo teaches:

Only one who frees his mind from desire is called a śraman. a. Only one who is not attached to the mundane world is called a renunciant (pravrajita). A practitioner wearing finery is like a dog in an elephant skin. A man of the way with hidden yearnings is like a hedgehog trying to enter a mouse hole. "

You have conquered your dependency for dreaming, but tell me Active Seeker, just what are you looking for? Are you looking for what will free your mind, and you, from this burning wheel? From this burning house? Or are you foolishly pouring oil upon its flames? Here, sick man, is the medicine. Why do you dig for poison? Perhaps these words sound fine to you, and good for showing off -- yet, Active Seeker, what keeps you from the prime opportunity is the realization of emptiness -- the emptiness of words is such that any profit from them, any true substance, is in the commitment to action -- not in the repetition.

In the latter days of summer, the mountain rains had ceased, and the moss along the monastery stones glowed with life. The cicadas chanted their tireless mantras, and the air smelled of rain-washed earth. In the courtyard, under the ancient fig tree, Shifu sat alone with a wooden bowl, grinding herbs.

A young man arrived. His robes were clean, his posture noble, his eyes bright with the eagerness of one newly devoted to the path. He had been called the Active Seeker by others, for his diligence was unquestioned. He read sutras aloud each morning before dawn. He fasted on the lunar calendar. He quoted the ancients with perfect pronunciation.

And yet, he was not well.

“Shifu,” the young man said, bowing deeply, “I have come with another question.”

Shifu did not speak at first. He only looked up, the grinding still in his hand. His eyes—those quiet embers—rested on the seeker’s face not with judgment, but with sorrow.

“Another one?” Shifu finally said.

The seeker nodded. “Yes. About emptiness. About intention. About—”

But Shifu raised a hand. “Let me tell you something, boy.”

He stood, slowly, and walked across the courtyard to the medicinal garden. The seeker followed.

“You see this plant?” Shifu asked, pointing to a low-growing herb with purple leaves. “That is duanchengcao—snake-stopper weed. Used for purifying the blood.”

The seeker nodded. “I’ve read about it.”

Shifu bent low and pulled another plant from the base of the same garden bed. It looked nearly the same.

“This,” he said, “is sǐrénhua—the poison that mimics the medicine. Indistinguishable, unless you’ve worked the field, tasted the bitterness with your own tongue. I have seen sick men who were given the cure—who walked right past it, and dug for this instead.”

He threw the poisonous root at the seeker’s feet.

“Why do you dig for poison, Active Seeker?” Shifu asked, voice rising not in anger, but genuine sadness. “Why do you insist on repeating words when you have not yet lived them?”

The seeker said nothing.

“Do you want relief? Or recognition?”

“I want freedom,” whispered the seeker.

“Then why are your hands still clutching doctrine like gold? Why do you polish the bottle, but never drink its contents?”

Shifu looked down at the herb bowl.

“Here is medicine. The Dharma is not a parable. It is not a poem. It is food and fire and blade. But you…”

He knelt and placed the bowl gently on the stone.

“…you treat it like incense. A thing to make you feel wise while you die of the same hunger.”

He stood and began to walk away.

Then stopped.

“You have conquered your craving for dreams, child,” Shifu said without turning, “but you have not yet conquered your craving for meaning.”

The Old Man and The Prime Opportunity

Shifu said:

"Listen well to Master Wonhyo one final time, the venerable has something wise to impart:

"A broken carriage does not roll, and in advanced age, you won’t practice. Lying down, you get lazy, and sitting brings distraction. How long will you live not cultivating, vacantly passing the days and nights? How long will you live with an empty body, not cultivating it for your whole life? This body will certainly perish—what body will you have afterward? Isn’t it urgent?! Isn’t it urgent?! "

Broken carriages, broken enough times, become almost impossible to repair -- and when there is no hope for them, their spare parts are all that remains. So too with the skandas, as the Buddha teaches. When all our parts reassemble, and when the breath returns, there it is Prime Opportunist -- there, the chance to practice. Do you feel the urgency? Do you feel the wind blowing, flowing through you?

Absorb now what is useful, soak it up like a sponge. Discard, drop, and destroy everything that is useless to you. And when it comes time to look deeply inside -- do so, finding in there what is uniquely your own to cast overboard, that you might row safely to the other shore and join the ranks of the trackless, who look upon the stream no longer.

There once lived an old man in a sun-baked village at the base of a narrow mountain pass. Every day, he would sit beside a broken carriage—once finely made, its wheels now split, its yoke rusted, the wood softened by rain and insects. No horse had drawn it in many years.

Pilgrims and traders passed him often, curious. Some asked, “Why do you keep this broken thing?” The old man would wave them off. “It has meaning to me,” he’d say. “I will fix it when the season is right.”

Seasons changed.

Decades passed.

And the man grew weaker, though he still talked of the day he would ride again—how he would ascend the pass and see the mountaintop temple with his own eyes. “Just a few more nails, a fresh wheel,” he would mutter, watching the stars from the comfort of inaction.

One morning, a young traveler arrived—thin, dusty, but bright-eyed. He asked the old man if he might borrow the wood from the broken carriage to finish building a raft. A great river crossed the traveler’s path, and he needed to move forward.

“Take it,” said the old man with a strange softness. “It never took me where I promised myself I would go.”

And as the traveler removed the final pieces of the ruined carriage, the old man looked upon the empty space and whispered:

“That was my body, my chance.

And I used it for waiting.”

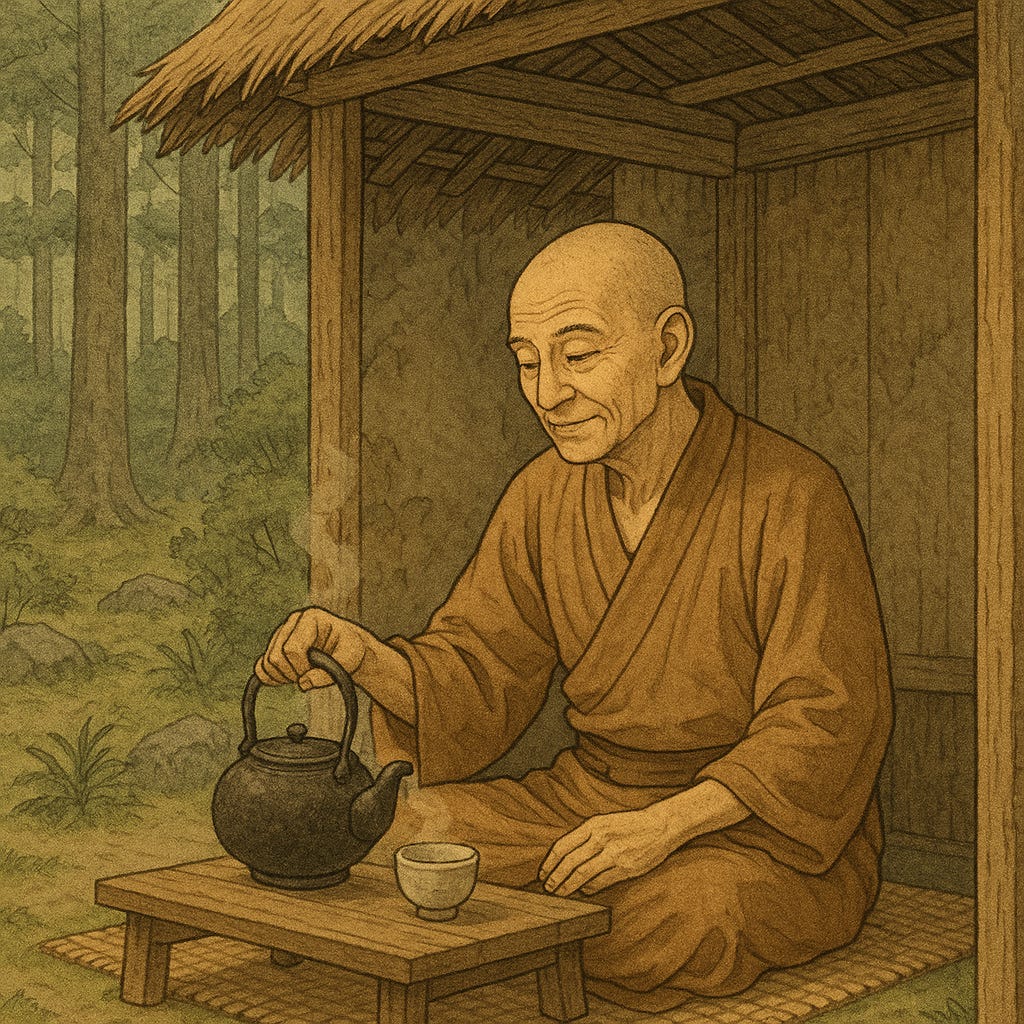

The Taste Of Tea

My father said: "I have heard many claim to be enlightened, but who are still deep in slumber. I have met many enlightened who, like pratyekabuddha, never wished to shine a light upon themselves -- or who, like bodhisattvas, shunned the light of fame because it got in the way of their salvific works. Will I reach nibbana, will you? This I cannot say -- only that the tea has been steeped, and it is smelling delicious"

There was once a monk who wandered without companions, carrying no bowl, no bell, no sutra scroll. He stopped wherever the path ended for the day, and rested wherever he found a stone or a fallen log. Villagers called him The Silent One, though he was not mute — he simply did not speak unless what needed to be said could not be left unsaid.

One day, a novice approached him, eager, fiery-eyed.

“Master!” the novice cried, “I have studied the Vinaya, chanted the Prajñāpāramitā, and sit for hours in zazen. My teachers call me awakened. They say I am on the cusp of enlightenment. Do you think I am close to nirvāṇa?”

The Silent One smiled.

Then said nothing.

The novice pressed on, agitated. “Do you know enlightenment? Have you reached it?”

Still smiling, the Silent One gestured to a kettle boiling on the fire nearby. He poured hot water over leaves in a plain clay cup. They sat together for a time as the tea steeped, the scent rising gently between them.

Finally, the Silent One spoke.

“Many boast of having fire,

But cannot even boil water.

Many claim they are the moon,

But hide behind clouds to keep from being revealed.”

He placed the cup in the novice’s hands.

“The tea has been steeped.

It smells delicious.

Drink when you are ready —

But do not ask me whether it will reach your tongue,

Or whether it will satisfy your thirst.

That part,

Is yours.”

And with that, he stood, and walked off into the forest, never seen again.