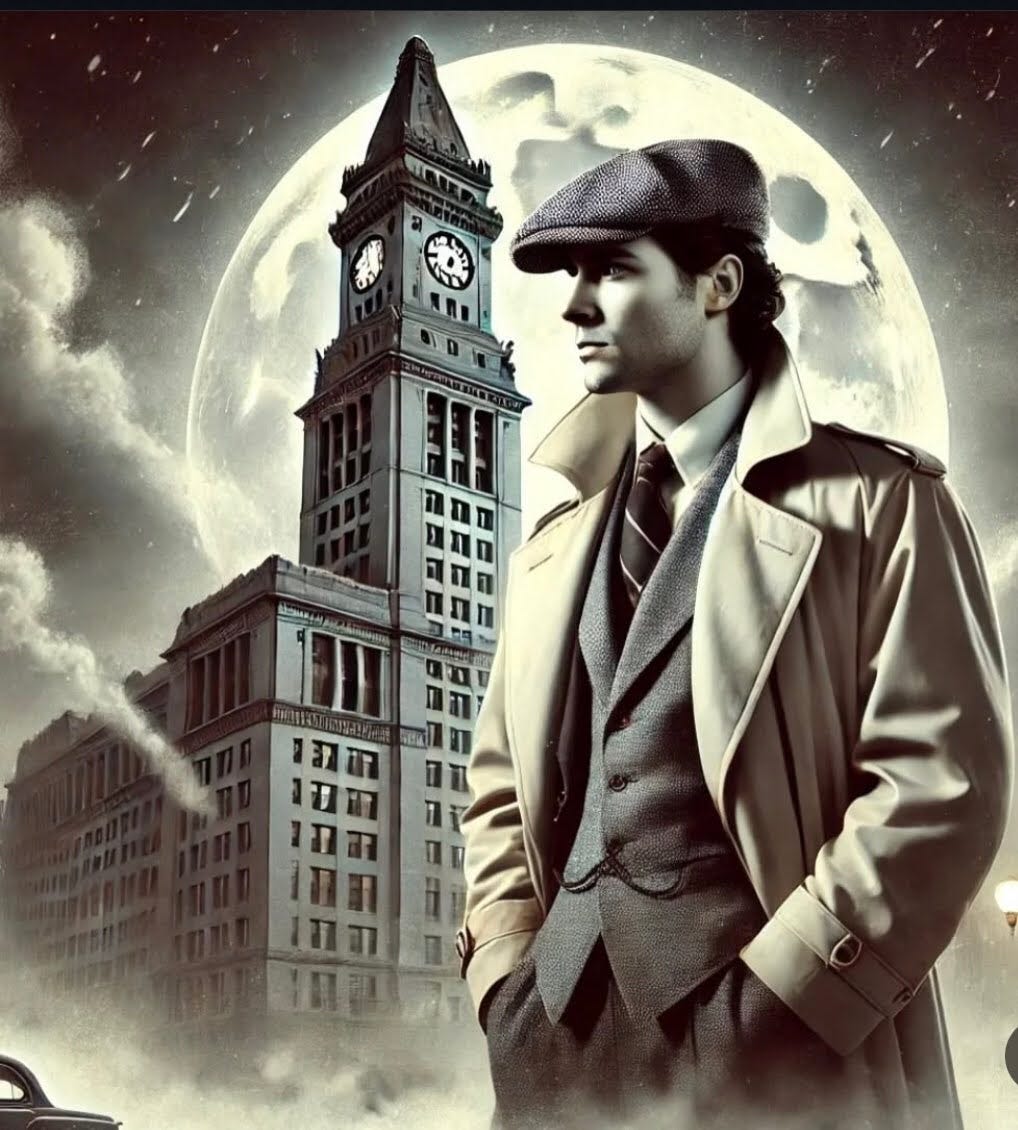

The Good Life: A Detective Joe Lupo Novella in Four Movements

Oh, the good life....full of fun, seems to be the ideal.

Smoke Trails

They say the North End never forgets. Not the priests and the friars, not the widows who keep their husbands' names alive through minestrone and processions to Central Wharf or the bocce court, not the old fishmongers whose knives have sliced more than just cod beneath the awnings on Fleet Street. And certainly not Battery Street, a charming definitely European-like nook in the neighbourhood, which still hums—on certain nights—with the rhythm of old shoes from Varese’s slapping the wet pavement, a sound that echoes like penance and perdition in the corridors of memory.

The scent still clung to the bricks: sweet pipe tobacco, the particular kind smoked by the kind old painter who’d passed away five, maybe six years ago. He used to sit just outside the library courtyard, brush in one hand, folding stool in the other, always offering Joe a smile and a nonno’s advice when the latter came by on his after-school pilgrimages. He’d told Joe once that a good painting was like a secret—you didn’t see it until you slowed down long enough to be trusted.

That smoke, impossibly, was still here. It curled in under the grill smoke, the garlic, the competing perfumes of women from Hanover Street weddings pouring out of the Peace Garden and Salem Street rendezvous. The scents did battle in the air, each one a claim on the heart of someone sentimental.

Joe Lupo lit his cigarette slowly, half from habit, half from ritual. Blueberry would be mortified and amused at the same time. The lighter’s flame briefly illuminated his eyes—those same tired green marbles he’d inherited from Sonny, just dustier now. He inhaled and let the smoke drift upward to meet the old painter’s spirit. A greeting.

Across the street, someone laughed—one of those clean, office-polished laughs. Probably a couple finance guys from Boston’s FiDi, en route to a cannoli shop their girlfriends saw on TikTok. Joe didn’t hate them. They weren’t the enemy — the enemies never changed, almost like history.

Still, the North End didn’t sound like it used to, not to Joe anyway. Where were the two dozen “aunties” who were better than any modern surveillance system? Had they all moved to Stoneham overnight? Maybe. Where were the old men who spent so much time on the coffeeshop benches they almost seemed stuck like statues? Dead, most likely. Drinking cappuccino in the afterlife — only until 10 in the morning of course.

Even the shouting had changed. Gone were the evening squabbles between third-floor neighbors over parking or politics or a cousin's girlfriend who drank too much limoncello. Now it was newfangled baby strollers, delivery scooters, and the slow, eager hope of new families doing what new families always do to the North End—make it new again.

“Don’t listen to the curmudgeons, Joey,” Sonny used to say, stirring the Bolognese with flair on their Sunday afternoons. “This neighborhood? She’s not just for Italians. She’s for everyone and no one. She’s an organism. Now go put on my Spotify playlist, you know the one…with Tony Bennett.”

Joe smirked, he remembered nodding along back then, not fully understanding, but now—years and several chapters worth of regret later—he felt it in his aging, fragile bones. The North End wasn’t nostalgic; it was adaptive. She let you remember, but never quite the way it happened because, much like his mother, she was in a league of her own with those memories.

And tonight, the memory was a chase.

August 2014: Battery Street

Joe turned the corner slowly, eyes scanning the sidewalks as if time might be sitting there, legs crossed, smoking something Turkish.

The scent of incense still clung faintly to his memory, braided with that unmistakable basil-wood must that settled on your clothes after an hour in Saint Leonard’s. He hadn’t been inside the church in years, but the Vigil Mass still lingered in his mind like a half-finished hymn.

I always knew my dad loved his job, Joe thought, but I never knew how much he loved to run until that Saturday afternoon rushed onto the scene.

They’d just come out of Mass. Fr. Carlo had the kind of timing you rarely see in priests—half stand-up comic, half prophet. He’d made the entire congregation laugh mid-sermon by comparing Saint Peter’s stubbornness to an old Sicilian grandmother’s recipe routine. Even Sonny chuckled. Joe remembered they were both in good spirits, talking about it as they walked past the bell tower toward Sonny’s favorite watering hole on Atlantic Avenue, dreaming aloud about the mixed grill he always ordered—two kinds of sausage, a pork chop, steak tips, potaotes and peppers with just the right char.

And Jackie, the iconic Southie server — she always had the Sox game on. The good life. That’s certainly what it felt like as the bright oranges, reds, and yellows kissed the architecture and coloured the countless vignettes playing out before their eyes.

That’s when it happened.

The old lady with the shopping cart. She was practically a landmark herself as all the nonnas are —her old TrueValue shopping cart lined with tinfoil and orange peels, squeaky wheels, eternal mutterings about prices that only got higher everywhere you turned. She stepped into the street at the wrong time, and the car came fast—too fast. Rust-red. Windows rolled down. Music blasting something ugly.

She didn’t die, thank God. Just knocked breathless, her mouth forming a scream that never quite made it out. But Joe would never forget the look on Sonny’s face. Not until his mother passed, not until the nurse folded her hands gently on that starched white sheet, would Joe see that face again—contorted in sorrow, disbelief, and something harder.

“Fuck around and find out,” he muttered now, watching a family cross the same street, stroller wheels obediently bumping over the sidewalk cracks.

Back then, Joe didn’t know the driver’s name. Didn’t want to. Didn’t have the chance.

All he remembered was the roar of the tires as the car peeled away—and the immediate, thunderous answer of his father’s shoes against concrete. Sonny didn’t hesitate. He moved with a grace that felt ancestral, a sprint born not from adrenaline, but blood-right. The way he cut corners, vaulted trash bins, ducked under scaffolding—it was like watching someone spiral out, quite literally, in real time.

People turned. Shoppers, tourists, the Brazilian waiters from the trattoria on the corner—they all watched. Joe tried to follow. Of course he did. But he was always a few steps behind. He always had been. That was the theme of his life: chasing Sonny Lupo and never quite catching up.

By the time he reached the bottom of that small artificial hill at the Battery, the harbor light glinting like coins in a fountain, Sonny already had the man.

Hand gripped in the collar like a butcher handling a hog. A red-faced, glass-eyed drunk with breath like turpentine and eyes that looked… not afraid, but aware. Like he recognized Sonny. Like he’d expected to be caught. Still, he spoke the litany of all slimeballs:

“Eyy what the fuck ‘you doin? I ain’t done nothing wrong mister!”.

Joe chuckled, “a fucking cariacture of a crook” he muttered as he also remembered that smell, Christ that smell, fermented sweat, cheap cigarettes smoked to the filter, the thick rotgut fog of someone who’d lived too long on the fringe — and the worst part? He had family in the back. Of course he did. They always did.

The beat cops had shown up a few minutes later, huffing and nodding. One of them, Cawley, said something like:

“Go get dinner with Joey, Sonny. We’ve got this.”

And just like that, Rubio—the name Joe would only learn years later—was led away. Joe and his father went and had their mixed grill, and Sonny didn’t talk about it. He laughed about Fr. Carlo again. He loved how the guy used to sneak espresso into confession.

That was that.

……Or was it?

Present Day: Joe’s Apartment

Joe’s apartment wasn’t much, but it was his.

2nd floor of a pre-war building with real crown molding and fake marble tiles. He’d had it almost five years, and even now, he sometimes surprised himself by calling it home. It wasn’t New York at night. It wasn’t Istanbul. It wasn’t Sydney.

Hell, it wasn’t even the other side of the waterfront with its clean views and quiet lobbies — the kind you thought might break like a faberge egg.

But Joe’s place it…it was something.

He walked into the living room and felt the hush. The good kind.

The kind that doesn't accuse you of being alone—it just lets you be. The light hit just right in the early afternoon, golden stripes across the parquet. Dust floated like little questions.

Joe could still smell Blueberry in certain corners of the place.

Some trace of her perfume on the throw pillow.

A hint of her shampoo when he opened the hall closet.

He smiled to himself—loving, not longing.

On the counter sat the lunch Auntie Ava had delivered him, just as she had every day for years now, ever since she decided Joe was “too precious and too stubborn to cook for himself.” Rice pilaf.Exactly like his mother used to make, from the same steel pot, same thyme, same ratios which seemed random to the untrained eye yet were anything but.

Joe peeled back the foil, let the steam rise like a prayer.

He poured himself a glass of cherry cola—the cold hiss of carbonation a small ritual now.

No more alcohol. Not because of any clean-slate creed, but because it just didn’t make sense anymore. Especially not alone. A detective drinks when he needs to. He hadn’t needed to in a long time.

He sat by the window, forked a bite of pilaf, and watched the delivery bikes outside bob and weave like minnows in traffic. One of them cursed in Spanish. Another nearly hit a flower stand. Life doing its thing.

But the memory hit him like a shoulder check at South Station, near the Cajun takeout place — people loved the free samples.

It felt hard.

Sudden.

Inevitable.

Rubio, the red-faced drunk.

Why now?

He was supposed to be combing through case files for Oasis—the diagnostic reports, intelligence signals, those endless graphs.

He’d become more of a data scientist than a gumshoe.

Funny how that happened.

He smirked and shook his head. “The breakthrough engine,” he muttered aloud. What a phrase. Sounded like sciene fiction. But it wasn’t. Not really. It was saving people.

He looked over at Astra, his assistant—technically an AI hologram, but as real as anything else in his day. She was watching him from her digital pedestal, projected in soft light near the bookshelf. Bright green artificial eyes. Perpetually hopeful expression.

She tilted her head like a bird and said gently:

“You’re thinking again, Detective.”

He gave her a look.

She didn’t flinch.

She never did.

Blueberry had given him a box of roasted nuts for New Year’s.

“For my favorite nut,” she’d joked.

Astra had repeated the line so earnestly that it had initially confused him into silence.

She’d apologized profusely afterward, clearly wounded. Joe had never corrected her. He liked how concerned she got. It made her… almost human.

He popped one of the almonds into his mouth and leaned forward, looking out at the harbor.

And then it happened.

The click.

That internal shift like a tumbling lock.

It wasn’t the memory of Rubio himself. Not at first.

It was a song.

Tony Bennett.

“The Good Life.”

The original his father used to play on mornings, every damn morning without fail. First thing. Like clockwork.

Joe could hear the proverbial needle drop in his mind.

The hiss.

Then the croon:

“Oh, the good life… full of fun… seems to be the ideal…”

He closed his eyes, cherry cola resting cool on his tongue.

He missed the old man. And suddenly he could see the other guy, the crook, again—not in motion, not being chased, but after.

Handcuffed. Being led to the cruiser. That moment when Sonny turned to talk with the cops and Rubio glanced sideways.

At him.

Joe.

Seventeen years old, frozen near a lamppost, trying to look tough in his dad’s old jacket. Rubio’s eyes locked with his. It wasn’t long—half a second maybe—but it lingered.

It wasn’t a drunk’s stare, it was centered.

Wasn’t fear either — and it wasn’t courage.

It was recognition.

Like he knew who Joe was.

Like he’d seen him before.

Or would again.

Joe blinked.

He shook the thought off, sipped more cola.

The carbonation fizzed loud in the silence.

His phone buzzed.

Chief Jay Strauss had liked one of his data charts from the week before. The one modeling most of their strategies into visualizations that, admittedly, were pretty smart looking. Joe chuckled.

Another buzz.

Papa.

“Adding to the muffin tax. Am I ever going to see you?”

Joe smiled, guilt pinching his ribs. He hadn’t seen Sonny in too long. Kept meaning to. Work. Time. Excuses.

And then another ping.

This one made his stomach tighten.

Barbiano’s daughter.

Jennifer. An old friend. His old preschool teacher’s girl. Always sharp. Quiet. Poised like a mystery novel’s protagonist.

“Hey Joey. Remember that guy your dad chased down years ago? Rubio? Call me. I’ve got news.”

Joe read it twice.

And then a third time.

He looked out at the city. The sky had turned a pale bruised blue.

Rubio.

The name whispered again, like an unclosed door somewhere in the lofty crawlspace of the city.